Edwin B. Twitmyer

The Hope Circuit by Martin Seligman

Chapter 5, Twitmyer's Breakthrough

In the room that housed my desk in graduate school, one of the great fiascos of science had taken place sixty years before: Edwin Burket Twitmyer's announcement of his momentous discovery to the psychological world. It was not auspicious that my desk sat exactly there.

On the morning of December 29, 1904, the leading lights of American psychology assembled to listen to each other's papers. The occasion was the thirteenth annual meeting of the American Psychological Association (APA), held appropriately enough on the West Philadelphia campus of the University of Pennsylvania. Penn was home to the very first department of psychology in America, established in 1887. Its founders had taken inspiration from Leipzig's Wilhelm Wundt and his brave band of breakaway German-speaking scientists - brave because they sought nothing less than a science of mental states, a science of psychology. College Hall, a Victorian pile of green and brown stone, sat in the center of the few buildings that constituted the University of Pennsylvania. To attend the paper reading, these professors, the men wearing heavy dark suits and white shirts with rounded collars, trudged up the twelve concrete steps and through the heavy double doors. It is noteworthy that the assemblage was not solely male since the next APA president, Mary Whiton Calkins, was among them. They turned right, strode the length of the wide corridor with its fifteen-foot ceiling, and entered the large classroom.

On the dais sat William James himself, the newly inaugurated president of the American Psychological Association, holding that post for the second time. James was a founder of American psychology, having established the first American "psychological laboratory" at Harvard in 1875, even while teaching physiology. His was an aweinspiring presence. Erect and wiry, with striking blue eyes, his light beard now mostly gray, James was an affable and witty conversationalist. Like his dour brother, novelist Henry James, William was quite fragile, having suffered at least two "nervous breakdowns," and he was a prolific but much less fusty a writer than Henry. His acclaimed 1,200-page Principles of Psychology was already the classic textbook, and his influential essay "Does Consciousness Exist?" had just come out.

James called the morning session to order, and the reading of papers began. You, my reader, and even I would have found the session dull-our knowledge of what was about to happen notwithstanding - and we would have spent our time gazing out the twelve-foot windows onto the green fields. R. S. Woodworth reported a high correlation between the strength of the right hand and the left. Margaret Washburn discoursed on the difference between a "feeling" and a "sensation." Hugo Muensterberg somehow united the truth of arithmetic with the values of morality and religion. Lightner Witmer, director of the psychological clinic of the Penn department, reported on the accuracy of guesses about the heaviness of very similar weights. A polite, low-key discussion lasting about ten minutes followed each paper.

At least one person in the audience was terrifically excited, barely able to contain himself. Thirty-one-year-old Edwin B. Twitmyer was about to report on his 1902 doctoral dissertation. He suspected that he had captured the most fundamental particle of learning.

This was a grand venture with a venerable provenance. David Hume (1711-1776), the founder of "associationism," claimed that we could never observe cause directly; rather we could only observe the contiguity in time between two events. The red billiard ball strikes the white ball, and the white ball shoots off into the pocket. We infer that the motion of the red ball caused the white ball's motion, but all we ever see is an association in time. Such associations are the fundamental building blocks of all learning, since for the British empiricists, of whom Hume was the leading light, the mind is but a blank slate that experience writes on. And what does experience write on the blank slate? Only these associations, and so all that we learn, all that we know, is merely the combination of countless pairings.

This became a program for scientific psychology. If science could isolate and measure such associations in the laboratory, science would be able to measure learning objectively and get on its way to unraveling the mysteries of all knowledge. The scientist who discovered how to do this would achieve immortality.

Twitmyer believed he had done it. When the human kneecap is struck - just right - with a rubber hammer, a large kick ensues. This is called the patellar reflex. Reflexes are not learned; they are the nervous system's inevitable and unconscious reaction to a stimulus. Twitmyer, ingeniously, rang a bell half a second before each hammer blow. Sure enough after 150 or more pairings, the bell itself was followed by the kick - even before the hammer blow. This worked for every one of Twitmyer's six subjects.

This should all sound familiar, because in Saint Petersburg at just the same time and for similar reasons, Ivan Petrovich Pavlov was doing essentially the same thing - independently. Pavlov paired the clicking of a metronome with food powder injected into the mouths of dogs and found that the clicks alone came to elicit salivation. Pavlov added an important wrinkle: digestive surgeon that he was - not a psychologist - he extruded the salivary gland of the dog, and so he could count precisely the number of drops of saliva elicited by the clicks, rather than just weighing some mushy food. Pavlov, already renowned for his work on digestion for which he got the Nobel Prize in 1904, trumpeted these results in Madrid in 1903 in his Nobel acceptance speech. Pavlov achieved immortality for discovering this, the "conditional reflex."

Twitmyer did not achieve immortality. For at the close of his paper, James said, "Just in time for lunch. I guess there won't be any discussion of this paper. Let's go eat."

Why didn't Twitmyer get any credit at all for this important discovery? For one thing Twitmyer's 1902 dissertation was privately printed and so inaccessible, while Pavlov - already an international icon - was able to spread the word of his latest discovery in his Nobel acceptance speech. Twitmyer, in contrast, was a newbie and seems to have shyly avoided anything that smacked of self-promotion. For another, American psychologists at this time focused on consciousness, whereas a reflex was merely physical and mechanical, hardly the key that would unlock the mind. But it is also a sad fact that William James was bored and hungry.

Kneecapped, Twitmyer dropped his conditioning work and turned his attention to his wife's specialty, speech defects in children.

Sixty years later this wound to the collective psyche of Penn's proud department still festered, and I could sense it as Professor Francis W. Irwin related the Twitmyer story to us. Frank had been at the center of the only psychology coup d'etat of the last century. Since Twitmyer's time Penn's department had gotten sleepier and sleepier, and by 1955 it was snoring audibly. As the longtime editor in chief of the prestigious Journal of Experimental Psychology, Frank was one of the only faculty members who still had his finger on the pulse of any living science. He persuaded Penn's high administration that a rustling was in order, and the victim of the raid was to be Harvard's psychology department. Two rival tyrants then reigned over Harvard: B. F. (Fred) Skinner, the star of 1950s behaviorism, and S. S (Smitty) Stevens, the world's leading mathematical psychophysiologist. But chafing under their whip hands were a half dozen brilliant young psychologists. Penn contacted Robert Bush, the political leader of these young Turks, and in one fell swoop Penn offered all of them full professorships. All of them accepted, and you will meet this cast of characters shortly. Nothing like this had ever happened before in psychology; nor has it since. So in 1958 a rejuvenated department under the chairmanship of Bob Bush suddenly appeared at 121 College Hall. Penn became - overnight - the place to be.

Frank told us the Twitmyer story on the very first day of the proseminar, the grueling yearlong, five-day-a-week course in which every single faculty member taught, seriatim, his (pronoun accurate) personal research in detail. Frank (PhD, Penn 1931) was the senior member of the faculty, and he actually knew Twitmyer. Austerely dressed in a threadbare gray suit and gray-blue tie, he looked considerably older than his sixty years - although everyone over fifty looked ancient to me at the time. He chain-smoked and at one point had three cigarettes smoldering - he was every bit as nervous as the twenty graduate students newly arrived at the place to be.

He had every right to be nervous since he was presenting the culmination of his forty years' work on learning to a hypercritical audience. Young as we were, we were up to date about the very latest in learning theory - trends Frank was deeply skeptical about. He did not believe in stimulus-response-reinforcement theory, which held a monopoly in the field of learning.

Frank came to maturity as this monopoly grew. To appreciate why behaviorism came to exert over the world of psychology a hold so strong that Frank spent his entire career fighting it, let's return to William James's shooing everyone out to lunch.

William James was likely bored by the reflexes of the knee and for good reason. The associationists were thoroughgoing mentalists: an association was the pairing of two mental states: the idea of wooden false teeth evokes an image of the unsmiling George Washington. James believed that mental states - ideas, images, knowledge, attention, and awareness - were the true subjects of psychology. You can bet that James began to gaze out the window soon after the talk started, thinking that this Twit-fellow was irrelevant: no science of mind would ever come from low-level reflexes.

But James did not reckon on behaviorism, the up-and-coming movement that dispensed with mental life altogether on the grounds that only behavior can be reliably measured.

Seligman, M. E. P. (2018). Chapter 5: Twitmyer’s Breakthrough. In The Hope Circuit: A Psychologist’s Journey from Helplessness to Optimism (pp. 59–64). essay, PublicAffairs.

Obituary: Edwin Burket Twitmyer, 1873-1943

Edwin Burket Twitmyer, professor or psychology and director of the Psychological Laboratory and Clinic at the University of Pennsylvania was born in McElhattan, Pa., on September 14, l873, and died in Philadelphia, after a brier illness, on March 3, 1943, at the age or 69.

Twitmyer received his bachelor's degree from Lafayette College in 1896. In the Following year he became instructor in psychology at the University of Pennsylvania, and the rest or his career was spent at that University. There he received his doctoral degree in 1902, and there also he was appointed professor in 1914 and director of the Psychological Laboratory and Clinic in 1937. At the time of his death he was nearing the end or his 46th year or service at the University.

When Twitmyer came to Pennsylvania, the Psychological Clinic was in its early infancy, having been established by Lightner Witmer during the previous year (1896). His own interests were soon drawn into this direction, and he was active in the efforts which were successfully made to interest the public, and particularly teachers in the public schools, in the use of the clinic's facilities. His first wife, Mary Marvin Twitmyer, was a teacher or the deaf, to whom Witmer during the clinic's first year had turned for assistance in the treatment of a case of defective speech. From her Twitmyer derived an interest in this field; and in 1914 the special clinic for the treatment of speech defects was established with him as its head. To this work, thereafter, he devoted a large share or his energies. In Correction of Defective Speech (1932), written in collaboration with Y. S. Nathanson, he expressed the point of view to which he consistently adhered, that in spite or the great variety of organic and psychological correlates of disorders or speech, disturbances of the normal rhythm of breathing constituted the closest approach to a common etiological factor, that these disturbances were, in part, of an habitual nature, and that they could frequently be treated by methods designed to break bad habits and establish good ones.

The story of Twitmyer's doctoral dissertation is not without interest for the history of psychology. He began with the intention or studying the variability of the patellar tendon reflex under both 'normal' and facilitating conditions. During the course or the experiment, however, he observed by accident a more interesting phenomenon. He himself has described it in the published dissertation:

"During the adjustment of the apparatus for an earlier group of experiments with one subject (Subject A) a decided kick of both legs was observed to follow a tap of the signal bell occurring without the usual blow of the hammers on the tendons. ... Two alternatives presented themselves. Either (1) the subject was in error in his introspective observation and had voluntarily moved his legs, or (2) the true knee jerk (or a movement resembling it in appearance) had been produced by a stimulus other than the usual one.''

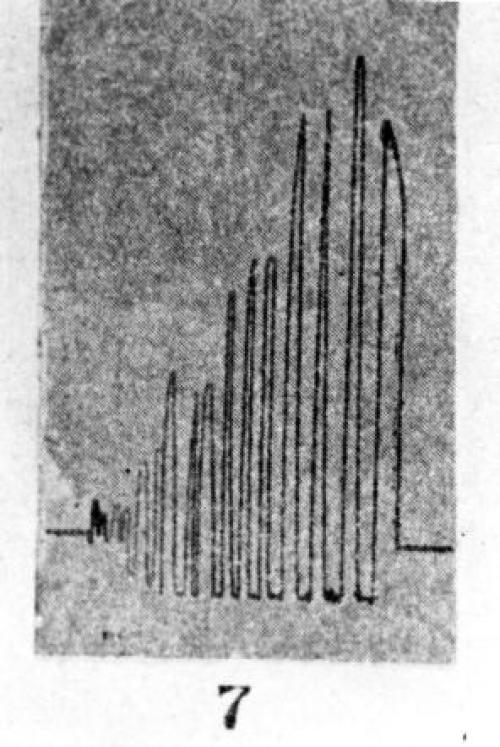

Further experiments convinced him that the phenomenon was not an artifact. It appeared in the case of each of the six Ss upon whom the experiment was attempted, although from 150 to 238 preceding trials with combined stimulation by bell and hammers were necessary. The stability of the response to the bell alone was round to be a function of the number of combined stimulations. No difference in the form of the graphic records of the new response and those of the normal knee jerk was observed, but he pointed out that such differences might require a faster-running kymograph to be made visible. Finally, not only did the Ss insist that the responses were not voluntary, but in some cases they found themselves unable to inhibit the response even though they made a great effort to do so. The report concluded with a statement of the intention to carry out further investigations of the new phenomenon.

To account completely for the fact that these investigations never materialized would require knowledge of matters not accessible to the historian. But more than this needs to be explained. As every psychologist knows, it was at this same time that very active and purposeful research was going forward in the laboratories of Pavlov and Bekhterev; and it is clear that in Pavlov's case, as in Twitmyer's, conditioning was first observed as an unexpected outcome of experiments which were directed toward a different end. Why should the history of conditioning have had its effective beginnings in the work of the Russians rather than among the psychologists of this country?

It is probably not sufficient to point to the obscurity of Twitmyer's work which resulted from his dissertation having been privately published. The findings of his experiment were reported before the American Psychological Association at its Christmas meetings in Philadelphia in 1904, with William James presiding. Twitmyer's own recollections of this occasion were always mingled with feelings of disappointment at the failure or his auditors to express interest in his results, of which he recalled no discussion whatever. In addition, psychologists in this country had abundant opportunity to read the abstract of this paper, published in the proceedings of the meetings [Knee jerks without simulation of the patellar tendon, Psychological Bulletin, 2, 1905, 43 f.]. Brief as it is, this abstract presents perfectly clearly the essentials of the discovery, a spark surely sufficient to fire the imagination of anyone who was adequately prepared for it.

In this last suggestion, probably, the historical moral is to be found. The intellectual climate in which lived the American psychologist of the first years of this century was such that Twitmyer's first thought, when his Subject A produced a leg-kick to stimulation by bell alone, was apparently the question whether the S's introspection was in error. Pavlov, on the other hand, was first or all a physiologist, not directly concerned with his Ss' mental processes; and, in any case, he was dealing with animal Ss whose introspections could not be asked for. His results, therefore, easily presented themselves to him as affording an objective means or studying the activity of the central nervous system. Twitmyer's results, however, fell naturally into the context into which he himself placed them: that is, as an interesting extension of the law of contiguity. It must be recalled that even in 1914, and while formulating the behavioristic program, Watson rather deprecated the use of Pavlov's methods for psychological investigations. Thus, we may see in this whole episode the manner in which scientific progress is affected by the investigator's point of view.

Although he was first and foremost a clinician, Twitmyer always retained his interest in experimental psychology. His conviction that laboratory experience was as necessary for the training of the clinical psychologist as that of the experimentalist was expressed in the emphasis which he placed upon the laboratory as a major part of the course-work even in the undergraduate's first introduction to psychology. For this his students have owed him gratitude. His personal qualities, also, were such as to make him to an unusual degree a focus of the affection and loyalty of his students, colleagues, and friends.

The University of Pennsylvania

Francis W. Irwin

From The American Journal of Psychology, 56, 451-453, 1943.